The European Demidoff Foundation is delighted to sponsor the publication of the forthcoming book by Professor Michail Talalay on Anatole Demidov's, 'Travels to southern Russia in 1837'. This will be the first reprint of the original 1853 Russian version and is scheduled to publish in November, 2024 by the publishing house, Indrik. Professor Talalay has been a long-standing and consistent friend of the European Demidoff Foundation since its founding in Lugano, Switzerland in November, 2022. Shown below is the English translation of the preface to the forthcoming publication:

Anatole Nikolaievitch Demidov was born in Moscow in 1813. This followed the family’s return from Paris following Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Anatole’s father, Nicholas Demidov, on his return to Russia, raised two militias for Tsar Alexander I, that he personally financed and led directly against the French invaders. The militias enaged with distinction and bravery at various encounters including at the Battle of Borodino. From an early age, Anatole Demidov was raised as a Russian patriot and loyal servant of the Tsar.

However, in terms of personality, Demidov was more French than Russian. He was primarily educated in Paris, spoke little, if any, Russian, and lived most of his time in Paris or at Villa di San Donato, that is located near Florence. His visits to Russia were infrequent and mostly prompted by requests received directly from senior members of the Tsar’s court.

Tsar Nicholas I, who ascended the throne in 1825, was displeased with Demidov given that he refused to live in Russia and regularly withdrew sizeable annual dividends from his industrial empire in Russia to finance an extravagant lifestyle in Europe. It is believed that Demidov's voyage to southern Russia in 1837 was motivated by two primary objectives: the first was to secure economic benefits both for Russia and for the Demidov industrial empire; the second was to secure the Tsar’s favour. In fact, Demidov dedicated the entire project to Tsar Nicholas I as well as financing the entire expedition at the great personal cost approximating 500,000 French Francs. In return, Demidov expected to be recognised as a loyal servant of the Tsar and to be bestowed with an appropriate ‘lofty’ title. Unfortunately, this second ambition would not be fulfilled.

The 1837 journey to southern Russia was a true scientific expedition consistent with those earlier taken, for example, by Peter Simon Pallas, who from 1793 -94 explored Siberia under the protection of Catherine the Great. As Demidov described in his travel diary, the main objective of the expedition was to undertake a mineralogical and geological survey of Russia’s new territories. These ‘new lands’ also brought great strategic and commercial benefit as Russia gained a southern port in the immediate vicinity of the Mediterranean. The new territories further represented a religious reconquest of lands that had long been within the borders of the Byzantine Empire. In the preface to the first edition of Demidov’s travelogue, he makes reference to the “wonderful conquest” of the southern region by Catherine the Great: “Imagine being in the Black Sea and being surprised to be bathing in a pacified and Christian territory”.

It was the economic benefits that most interested Demidov who hoped to discover new, expansive sources of coal that was replacing wood as the primary source of fuel for large-scale industrial production. Oil was another source of fuel that Demidov was eager to find and to exploit in the new territories. In the opening pages of his diary, Demidov explains that: “If nature has deprived these vast southern solitudes of fir and oak, perhaps the soil will prove less hostile, and a nascent industry will be offered coal, this new soul of the material world, which can now make a people’s fortune faster than gold”.

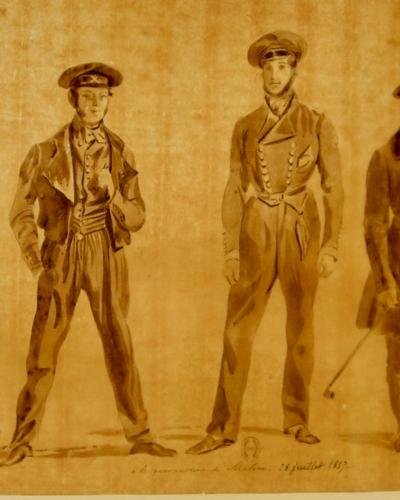

For the expedition Demidov assembled a group of twenty-two French technical experts from diverse scientific fields. They were organised into three separate teams each dressed in the distincitive blue uniform of the French ‘Ecole Royale des Mines’. The first team left from St. Petersburg and was led by Paul Kolounoff. Their mission was to explore, using drills, the coal seams that had been recently discovered in the land of the Don Cossacks.

This group eventually would be joined by a second team of French engineers who traveled directly east with a mission to find mineral deposits in the valley of the Donets River. This group was led by Frederic Le Play, professor at the French polytechnic in Paris.

The third team, whose mission included ‘the arts, natural history, and general observation’, embarked from Vienna on the coal-fuelled steamer, ‘Francois Ier’, and included, amongst others, Auguste Raffet and Auguste de Sainson, close collaborators and friends of Demidov. This group set-off on a more leisurely and pleasant journey floating along the Danube to eventually reach the Black Sea. It was Demidov who led this third group, accompanied by his lady-friend, the comtesse Fanny de la Rochefoucauld, who arrived with her French poodle.

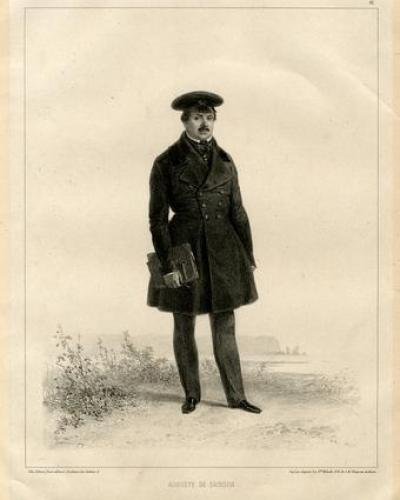

This third group would see a wide variety of picturesque cityscapes, dramatic landscapes, and engage with various diverse local populations. Demidov studied the various social systems encountered that included a review of the comparative penal systems that he found in these often lawless lands. Capturing the natural beauty along the scenic journey was the team’s artist, Auguste Raffet, a master of drawing and lithography. Raffet, like the French sociologist, Frederic Le Play, would end up spending years in Demidov's service.

Although the personal relationship between Demidov and the Tsar was cordial at best, Raffet’s reputation as a master artist preceded him. The Tsar most appreciated his artistic talents. In his diary, Demidov recounts that during a military review in the military colony of Voznesensk, near Odessa, the Tsar, recognising Raffet, called out to him to attend a personal audience with him and the Empress. Demidov, to his displeasure, was not invited.

As the painter of the travelogue, it was Raffet who selected, in close coordination with Demidov, each drawing to feature in the forthcoming publication. Both attempted to capture the most important images in order to provide an overall ‘picture’ of southern Russia. ‘Voyage dans la Russie méridionale et la Crimée’, published first in France from 1840 to 1842 in a sumptuous six-volume ‘large’ format comprised of four text volumes and two atlas volumes. The first text volume included Demidov’s travel diary, with certain sections written by Jules Janin and Auguste de Sainson, a frontispiece, two tables and one sheet of music. Also included were ninety-five hand-coloured lithographs and four large folding maps. The atlas included one hundred lithographs most by Raffet.

A small number of ‘Esquisses d un voyage dans la Russie méridionale et la Crimée’ also published that Demidov personally signed and gifted to his various hosts along the six month journey. For example, a recipient was the King of Bavaria, following a one day stop in Munich to view the King’s impressive collection of paintings. The publication of the large format series of books was then followed by the publication of a single-volume publication comprised of the diary and featuring over sixty of Raffet’s lithographs. These published in the UK (two-volume set), France, Italy, Spain, and, finally, in Russia. The Russian edition was not published until 1853, so over ten years following the publication of the original French version. The Tsar found this delay disrespectful. In the end, this meant that Demidov's book would never be reprinted in Russia. That is why, to this day, the publication is little known to the Russian reader.

As mentioned, one of Demidov's key objectives in mounting the six-month voyage of discovery to Russia's new lands included securing the Tsar's favour. However, for the Tsar, the expedition was a French initiative, led by Frenchmen, who all dressed in French uniforms. The work published first in France and in French. The long delay with the release of the book in Russia and in Russian was seen as a discourteous gesture. In the eyes of the Tsar, this showed that Demidov did not deserve any special favour. The Tsar did grant Demidov a ‘title’ for his efforts, but the low, modest rank of ‘College Councillor’. There would be no other testimonials of appreciation extended by the Tsar.

However, in regards to the first objective, the expedition did prove an overwhelming economic success. By the end of the 1830’s, the predominant fuel for heavy industry had shifted from wood to fossil fuels and, in particular, to coal. However, coal mining in these regions would need to wait until the 1870’s before expanding exponentially. By 1913, the coal mined from Donetz accounted for 87% of the Russian Empire’s total coal production. It goes without saying that today, these fossil fuels, are crucial to the functioning of the modern global economy.

Of course, today, and following centuries of rampant global industrialisation, we realise that this success has gone too far. It is generally accepted that if we are to safeguard our planet, the world does need to move towards lessened dependency on fossil fuels. However, it was Demidov, back in the mid-1830's, who had the foresight to correctly predict the potent impact of these sources of new energy to drive economic growth. Demidov actively and successfully pursued his dream of seriously exploring and exploiting these new sources of fuel to power both his industrial empire as well as that of the country. In this regard, there was no miscalculation.