Prof. Dr. Vitaliy Zherdev

L’Università degli Studi di Urbino Carlo Bo

Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts

The heritage of a short, yet brilliant, residence of the Demidoffs in Florence can be traced even today. A unique carved wooden decoration in the Russian Church of Nativity and St. Nicholas Thaumaturgus in Florence is also a part of the Demidoffs’ heritage. It is not only the massive carved gates to the upper temple that immediately draw the attention of the visitors, but the main part of the masterpiece by Italian woodcarvers in the lower temple. A marvelous iconostasis and icon-cases of full height icons of the apostles, utensils, and a large number of icons were given to the Florentine parish in 1879 from the former Demidoff family chapel.

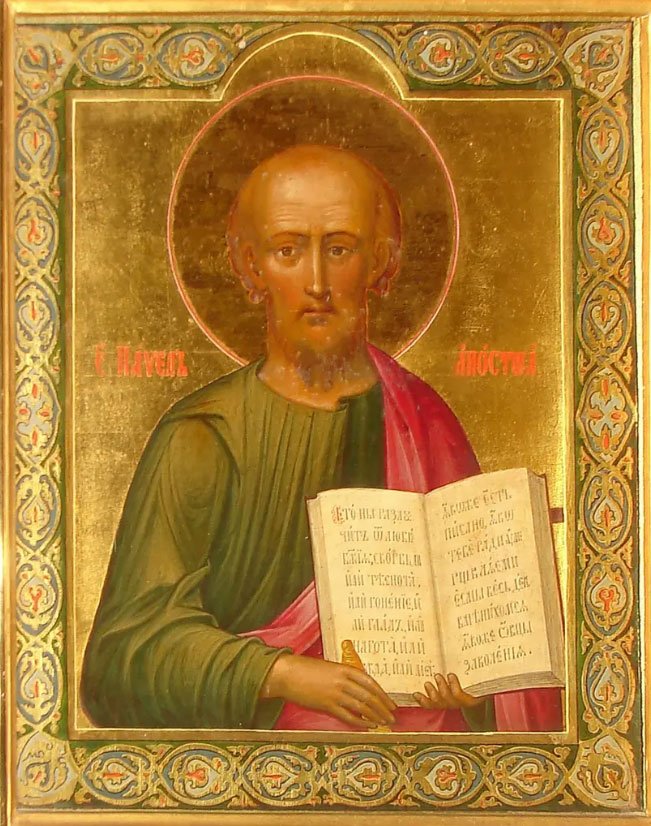

In the iconostasis, carved at Barbetti’s workshop at the commission of Prince Anatoly Nikolaevich Demidoff (1812 – 1870) and currently housed in the lower chapel of St. Nicholas Thaumaturgus, special attention is drawn to a gallery of small icons in the style of the 17th century. The icons are painted on a smooth golden background with marginal engravings imitating cloisonné enamel. Scattered patches of color represented by the clothes of holy patriarchs and royalty are rich with golden details, the curves are stylized in the icon-painting tradition. Some faces are painted quite realistically, combining iconic features with light-and-shade three-dimensional effects. The icon gallery counts twenty-seven images.

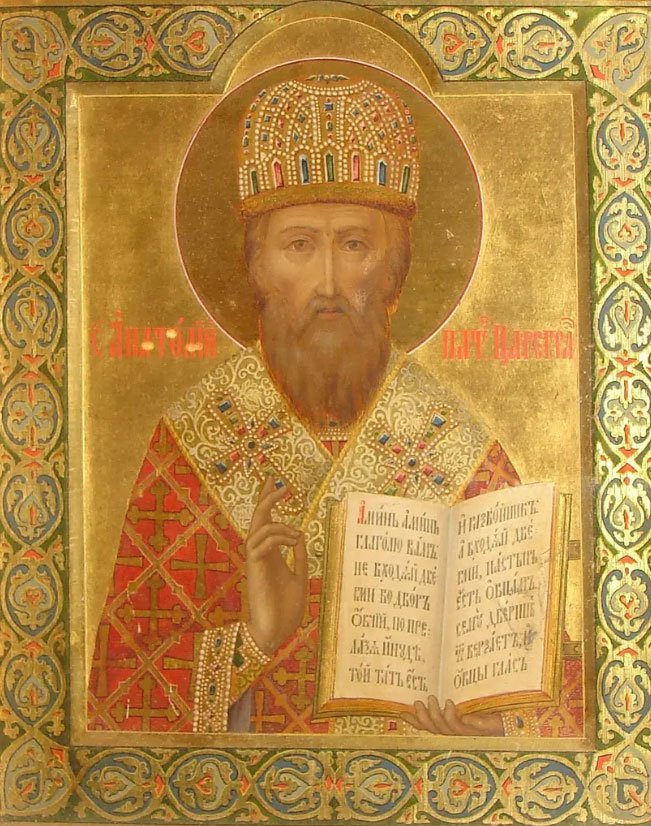

Some of them were integrated into the iconostasis along with the academic paintings by V. Vasilyev. In the second tier of the iconostasis one can see the icons of St. Abanoub (Onuphrius) the Great (presumably, the patron of the family of Antufyievs’ (Demidoffs), St. Mary Magdalene, St. Queen Alexandra and St. Hyacinth the Martyr (probably a dedication to Akinfiy Demidoff, the founder of the mining industry in the Urals and Siberia). On the right of the iconostasis: St. apostles Paul and Peter (fig.1, 2), St. Anatolius, patriarch of Constantinople (fig. 3). On the left: St. metropolitan Alexius, St. Gregory Nazianzus, and St. Elisabeth. There were also carved twin icon-cases in the Demidoff chapel, which were later altered to serve as doors (according to point 4 of the report on the temple building № 61 of 11 (24), 12 (25), 13 (26) 1901) 1 and placed onto the northern and southern service rooms of the upper church narthex.

The following icons were installed into the said doors / icon-cases. The northern ones: St. Catherine of Alexandria in the cartouche above the door leaf, St. Evangelists Matthew and Mark in the upper part of the leaf, St. Prince Alexander Nevsky, St. Emperor Constantine in the lower part, with St. Princes Vladimir and Olga equal-to-apostles on the back. The southern doors: St. Anatolius, patriarch of Constantinople in the cartouche, St. Evangelists Luke and John the Apostle in the upper part of the leaf, St. Andrew of Crete and St. Dmitry of Rostov in the lower part. On the back: St. Sergius of Radonezh and St. Anna the Prophetess. Also, three smaller icons are installed above the icon-cases of apostles Thomas, Matthew and Bartholomew in the lower temple.

As there is still no reliable information on the origin of the small icons, we can talk about the following hypotheses that require further documental and stylistic analysis. The first hypothesis to be discussed, despite it being somewhat “extravagant”, is as follows:

Since the distinctive icon-painting schools of Yaroslavl, Palekh, Mstera, etc. still existed in the 19th century, Prince Anatole Demidoff’s order could have been completed by the masters of these schools. However, the small icons from the Demidoff chapel are also very close in style to later examples of Nevyansk icon-painting. The fact that by the mid-19th century the distinctive icon-painting oriented to ancient examples still existed among Old Believers, who had once concentrated in the Ural properties of the Demidoffs, also counts in favour of the idea that the entire gallery of the small “Demidoff ” icons was made by the Nevyansk masters.

It is in the Urals, where the Russian mining industry takes its origin and where the adepts of the old order and the keepers of the old faith had fled from Peter’s reforms, that the original school of icon-painting began to develop. The town of Nevyansk that grew around the Demidoffs’ iron mill became central to the Old Believers community in the Urals. It was Akinfiy Demidoff who built an Old Believers’ monastery in the outskirts of Nevyansk at his own expense.2 The Demidoffs invited masters from Tula and Olonets factories where Old Belief flourished, they established close contacts with Old Believers’ circles from Kerzhenets and Vygovsky hermitage, and provided work to fugitive schismatics without interfering into their religious practices. According to the census of 1747, the Old Believers constituted almost half of the population of the Demidoffs’ towns-factories.3 This gave a start to the distinctive Nevyansk icon painting school, which enjoyed its best days during the peak of economic and industrial development of the region from the mid-18th until the mid-19th century.

The concept of “Nevyansk icon” is somewhat conventional and cannot be tied to one city, yet Nevyansk masters carried out orders throughout the region, and thus their style spread up to the Southern Ural. Nevyansk school relies on the traditions of the 17th century icon painting, which became a protograph for all of the later iconography, and tends to resemble Yaroslavl, Rostov and Kostroma iconography. The Nevyansk Icon is characterized by refinement and elegance of poses, fine modelling of faces, detailing and abundance of graphic decor.4 But the Old Believer milieu gradually absorbed both the influence of the official church and the external secular influence, which affected the style of the late Nevyansk icon painting, — the “archaic” features began to disappear and the realistic approach became more and more apparent. The icons from St. Nicholas Church in the village of Bynghi near Nevyansk are a vivid example of this. The church itself was built in 1789–1797 in a mixed style of the fading Baroque and Classicism. The icons that were created around the same period are nevertheless mostly made by Nevyansk masters in the spirit of the 17th century. The sophistication of the painting manner, the “refinement” of certain images (for example, the archangels on the deacon’s doors of the central iconostasis, the icons from the iconostasis of the southern chapel) are stylistically close to the images from the Demidoff Chapel.

As the wealth of the Old Believer merchants and industrialists increased, the Nevyansk icon began to evolve towards decorative art, becoming an item of luxury to embody the wealth of the Ural descendants and gold miners.5 Therefore, ordering from the Nevyansk icon painters a gallery of icons of saints, some of which bear the names of the founders of the Demidoff dynasty, becomes a very symbolic and independent gesture. Indeed, the Nevyansk factories were owned by the Demidoffs for a relatively short time — from 1702 to 1769 — and were sold by P. A. Demidoff — the grandson of Nikita Demidovich Antufiev — to the industrialist S. Y. Yakovlev (Sobakin).

However, by ordering icons from the masters of the Nevyansk school, Prince Anatole Demidoff could stress his connection with the former Ural patrimony that originated from the great founder of the dynasty. Besides that, the Nevyansk icon becoming more and more of a luxury item, it put emphasis on the customer’s high status as one of the richest people in Europe. The order being made by none other than Prince Anatole Nikolayevich is indicated by the fact that the gallery of small icons contains two images of St. Anatolius, the patriarch of Constantinople. Most likely, the time of this order coincided with the creation of the iconostasis and full-length images of the evangelists.

The other hypothesis is more probable. Since V. V. Vasilyev’s training as an artist began in the workshop of M. S. Peshekhonov 6, he certainly knew the basics of icon painting. This is evidenced by the icon of the Mother of God “Joy of All Who Sorrow” painted by Vasilyev in 1891, now in the collection of Yaroslavl Art Museum.7 This is an exact copy of an earlier icon with an interesting history, yet it shows that the artist possessed excellent technique and knowledge of the style. In 1858, Vasilyev received the title of Academician “in Byzantine style painting”, so it is interesting that the inscription — most likely made by the customer — on the back of the icon stated: “… the icon … was made by the icon-painting art of the artist of the Academy of Byzantine painting Vasily Vasilyev…” .8 By employing Vasilyev, the customer got in touch with a certain painting community, to which belonged the Peshekhonovs — by the way, a well-known Old Believer family. In 1856, the son of the workshop founder, V. M. Peshekhonov, was granted the title of Icon Painter of the Court of His Imperial Majesty.9

The high rank could be achieved through executing works for the court for at least eight to ten years — in person by the one claiming the title and, of course, at an a exceptional level. The icons made by the Peshekhonov workshop were known, in addition to the virtuosity of the execution, for their high cost. But ordering the icons from Peshekhonov was also a matter of prestige, which could have been Anatole Nikolayevich Demidoff’s motivation.

The Peshekhonov icon is characterized by its emphasis on the use of gold: golden backgrounds, golden ornaments, spaces superimposed by gold. Gold embossing was used, particularly, the framing (margins) was minted, the paint put on certain parts of the frame imitated the cloisonne enamel. Clothes were painted over gold, which allowed “scraping” to form various patterns on the fabric. Then, the diverging pattern was used to imitate the texture of rich embroidery. Face (lic’noe pis’mo) and dress (dolic’noe pis’mo) painting was performed by a multi-layer technique of tempera painting or mixed technique, in which oil and egg media were applied layer by layer. It is of note that V. Vasilyev also used the techniques of Peshekhonov’s style, in particular, rich engravings on nimbi and details.

Both of the hypotheses outline the avenues for future research and attribution of the small icons from the gallery of the Demidoff Chapel.

1 Levitskii, Vladimir. “Zhurnal sooruzheniia russkoi pravoslavnoi tserkvi vo Florentsii. 1897–1912. Prilozhenie 1”. In Talalai, Mikhail. Russkaia tserkovnaia zhizn’ i khramostroitel’stvo v Italii, 193–287. St. Petersburg: Kolo, 2011. (In Russian)

2 Shkerin, Vladimir. “Zakrytie staroobriadcheskikh chasoven v Nizhne-Tagil’skom zavodskom okruge v 30–40-e gody XIX veka”. In Religiia i tserkov’ v Sibiri, edited by A. Chernyshov, 94–102. Tiumen’: MI “RUTRA”, 1995, iss. 8. (In Russian)

3 Ebid. P. 94.

4 Golynets, Galina, ed. Nev’ianskaia ikona. Al’bom. Ekaterinburg: Ural’skii universitet, 1997. (In Russian)

5 Gramolin, A. “Nev’ianskaia ikonopis’”. Nauka i zhizn’, no. 8 (1998). Accessed April 23, 2018. https:// www.nkj.ru/archive/articles/10974/. (In Russian)

6 Khristianstvo v iskusstve, sm. Vasil’ev Vasilii Vasil’evich (1829–1894). Accessed June 08, 2018. http:// www.icon-art.info/author.php?lng=ru&author_id=139&mode=general. (In Russian)

7 Kuznetsova, Ol’ga, and Aleksei Fedorchuk, comp. Pokhvala Bogomateri. Ikony Iaroslavlia XIII–XX ve- kov iz sobraniia Iaroslavskogo Khudozhestvennogo muzeia. Katalog vystavki. Moscow: Severnyi Palomnik, 2003. P. 73-75. (In Russian)

8 Ibid. P. 75.

9 Belik, Zhanna. “Ikonopisets Dvora Ego Imperatorskogo Velichestva”. Russkoe iskusstvo, no. 3 (2006). Accessed June 17, 2018. http://www.russiskusstvo.ru/themes/artist/a1858/. (In Russian)