The discovery of art, which over the centuries was looted in times of war and revolution; or following the art-object’s disappearance from view due to misplacement, negligence, or arrogance by people or simply a change in fashion… is the subject of this essay.

Art discoveries do not happen accidentally; and on the road to them, one must learn, study, read, research, observe, develop taste and philosophy – train oneself at it like an olympian before competition – all in all, be ready when a discovery emerges… Maintain discipline, focus, and not let anyone divert you from this task.

___________________

Eugene Edelman

Hollywood, 2023

On the Road to Count Demidoff

I was always fascinated by the role of destiny in the lives of people but also that of their art-possessions. More than the “patina” of age, or their incomparable craftsmanship, for me, the allure of an antique lies in its mysterious past life. Who made it? For whom? Why did the art-object separate from the owner? Especially watching a classic movie, the set-designs and decoration intrigued me… I often wondered about the objects whose authenticity it depends on to bring veracity to the story told… Are they Silent Stars in their own right?

The mystique of an “object of art” ending up in a movie is an extraordinary fact because before its new role it had proper artistic and historical importance. When placed in the fantasy of a movie it looses the original “pedigree”, for possible fame… thanks to great Hollywood personalities of the past who have demanded their movie-sets be made of original antiques. It is summarised in a statement by one great Hollywood personality, Eric Von Stroheim : “the camera could not lie…”.

ART PART OF A PROP

With the help of movie-historian Marc Wanamaker, our research indeed revealed that Hollywood studios began purchasing original art, for their props in the movies, as early as the beginning of the twentieth century. Thus – and it was a privilege to see many ‘old’ Hollywood-made movies – if I spotted an interesting object, Marc would identify for my further research, their date and production company.

MININ & POZHARSKY

Once, I was surprised to see in the set-design of an obscure 1949 movie, “Rusty Saves A Life” by Columbia Pictures, the sculpture of “Minin and Pozharsky” (appearing as a clock) closely modelled after a prominent and powerful monument in the famous Red Square in Moscow. [1.See enclosed]

The subject of the monument and clock depicts the Russian patriots Kuzma Minin and Prince Pozharsky who lead the Nizhni Novgorod volunteers against the Polish invaders in 1612. “Minin and Pozharsky”’s monument was the first ever to have been erected in Russia, and incarnates two distinct events in the history of the country. [2.See enclosed]

It was commissioned in 1804 by the residents of Nizhny Novgorod to celebrate the foundation of the Romanov dynasty as the first Tsars of a centralised Russia, after Moscow was liberated from the occupying Polish troups by Nizhny Novgorod volunteer-leaders of the Russian militia, Kuzma Minin and Prince Pozharsky, in 1612… The competition was won by the sculptor Ivan P. Martos (1754-1835) in 1808. It was installed also as a memorial to the victory over Napoleon in the Russian patriotic war of 1812, two centuries later.

The subject of the monument’s relief on the pedestal remains (as on the clock’s pedestal) – of the Russian people who gave away their possessions in an effort to save the country from invaders. The two young men on the left side depict the sons of the sculptor, Ivan Martos.

It appeared that the Hollywood studio effectively owned a reduction of Martos’ sculpture (discreetly incorporating a clock)!

The research into this apparent Minin and Pozarhsky clock lead me to Russia, Tsarskoe Selo (Catherine Palace) museum’s inventory, where an identical example, attributed to Thomire, is recorded “in patinated bronze and on a sienna-marble base”. Their information states that it was purchased by the Russian Government in 1821 for the apartments of Alexandre I designed by architect V.P. Stasov (1769-1848), and executed after a larger clock (their clock being a reduction in size) in gilt bronze on a malachite base made in around 1818-20 and signed by the best bronzier in Paris, Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1751-1843), on the order of Count Nicolas Demidoff. It also states several other examples were made.

Noteworthy, the Minin and Pozarhsky clock model was being reproduced in Russia since a law of 1822 strictly prohibited the import of any bronze objects from Europe to Russia: there is a record of a bronze manufacturer and merchant by the name “Alexandre Guirin” who, in 1829 exhibited a copy, by his own hand yet stamped “Thomire”, at the Manafakturny Exhibition in St. Petersburg.

… Could the Minin and Pozarhsky sculpture-clock seen in several Hollywood movies, belong to this production?

DEMIDOFF FAMILY

I was acquainted from historical knowledge with the great collector and philanthropist, Count Nicolas Demidoff (1773-1828), who ordered the Minin and Pozarhsky clock. He had supported the Patriotic War of 1812 by financing an entire regiment against the invading French troops of Napoleon, and lead this regiment in the Battle of Borodino. The family owned significant mining interests in the Urals after completely reorganising the production of firearms in Russia. The founder of the Demidoff fortune, Nikita Demidoff (1665-1725), was born from a family of blacksmiths and the family ennobled by Peter The Great for their important role in arms’ manufacturing.

His grandson, the Count Nicolas, became member of the Imperial Guards, “Aide-de-camp” to Count Potemkin in 1789, and participated in two campaigns against the Turks before becoming Chamberlain to Catherine The Great in 1794. By 1802 Count Nicolas was residing in Paris. He returned to Russia in 1812 because of Napoleon’s invasion but after Napoleon’s fall at Waterloo on June 18th 1815, he made Paris his home. Prior to this he donated his collection of paintings (which remarkably survived the burning of Moscow in 1812) to the city’s University. Following his wife’s death in 1818 (Elizaveta Stroganoff’s father was Minister of Arts in St. Petersburg) Count Nicolas left Paris for Rome, and Florence. In 1824 he was appointed Russian Minister to the Tuscan Court, and given the title of “Count of San Donato” by Leopold II, Duke of Tuscany. He purchased a marshy area near the Church of San Donato in Polverosa, shortly before he died in 1828, where he begun to build the lavish “Villa San Donato”.

Count Nicolas’ eldest son, Paolo (1798-1840), inherited San Donato but sent its contents to adorn his residence on Bolshaia Morscaia Street, in St. Petersburg. The extensive art collection contained five hundred masterpieces alone… and many sculptures and decorative arts…. Upon Paolo’s death in 1840, Count Nicolas’ younger son, Anatole (1812-1870), brought the collection back to San Donato.

PRINCESS MATHILDE BONAPARTE

Obsessed with the Bonaparte family, Anatole was assembling an extensive body of napoleonic art in honour of the man who had invaded Russia, even going so far as marrying Princess Mathilda Bonaparte (1820-1904), the daughter of Napoleon’s brother, Jérôme! [3.See enclosed]

Princess Mathilda was originally to marry Louis-Napoleon — son of Louis Bonaparte and Hortense (Napoleon’s brother and Josephine’s daughter), and future “Napoleon III”; but as a Bonaparte, the prospect of returning back to France for Mathilde would be nil since the family lived in exile, and Louis-Napoleon was imprisoned in Ham. The engagement to him was cancelled. A marriage to the Russian and wealthy Anatole Demidoff was appealing to Mathilde because her great aunt, through her mother Catherine of Würthenberg, was married to Tsar Paul of Russia and as such was mother to the “Liberator of Europe”, Tsar Alexandre I (Mathilde’s cousin): as a wife to Count Anatole Demidoff “Prince of San Donato”, she, and her father Jérôme Bonaparte, could finally make their way back to France!

It seemed important to me to follow the episodes in the life of his youngest son and heir, Anatole, who had bought a villa on the Island of Elba and turned it into a museum of Napoleon’s relics! Anatole insisted on keeping as a mistress the Duchess of Dino… As Mathilde confronted her during a ball, at San Donato in 1845, Anatole slapped his wife on both cheeks. Mathilde fled to St. Petersburg the next day, where Tsar Nicolas I disgraced Demidoff forbidding him to live within a hundred miles from her, which he followed up with terms of separation in 1846. Husband and wife never met again.

After the Bonaparte family and Mathilde were allowed to return to France, Count Anatole’s devotion to Napoleon and the Bonapartes continued in the hope to touch his wife’s heart and he moved to France permanently.

DEMIDOFF ART SALES

In his endeavour to improve and update the San Donato fine-arts’ collection which he inherited from his father and brother, Anatole sold some artwork as early as 1839; privately, or at auction in 1851… 1863… 1868… In 1870 he pre-arranged for fourteen rooms to be “removed” from San Donato and sold while on his deathbed.

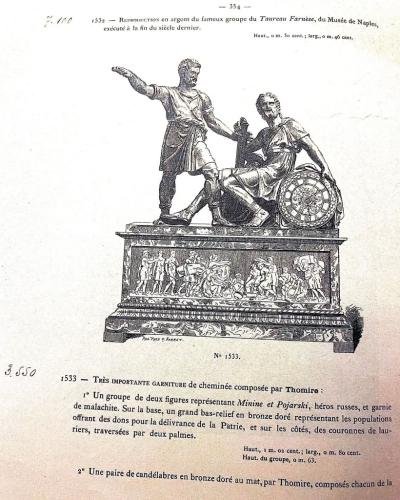

San Donato was finally stripped from its treasures in an ultimate and legendary “Demidoff sale”… in 1880.[4.See enclosed]. And appeared… in the March 15th 1880’s auction catalogue, by Charles Pillet, introducing the contents of “Palais de San Donato (…) Objets d’Art” : “Un groupe de deux figures représentant “Minin et Pozarhsky” héros Russes… et garni de malachite” – lot n° 1533, page 354. The lot is also illustrated with an engraving : it’s the clock in gilt bronze on a malachite base by Thomire!!! [4 bis.See enclosed].

This item was not placed in previous sales. It remained in Count Nicolas Demidoff’s collection as a personal symbol of his patriotism, until Paul (1839-1885), son of Paolo, dispersed all of Anatole’s Napoleonic collection in 1880.

It must have been considered too important, or indeed too close to Count Nicolas Demidoff’s heart to dispose of before the 1880 final sale.

Disregarding the existence of other copies (Ermitage, Peterhof, Paris/London auctions), extensive research into the whereabouts of the first and only Minin and Pozarhsky clock of gilt bronze and malachite by Thomire produced remarkable results: Count Nicolas who was considered the inventor of “Russian mosaic”, commissioned the clock to Thomire, and had it veneered in malachite from his Ural mines at Mednorudianskoe.

The clock is first documented in an engraving of 1820s, where it stands on a mantelpiece in Count Demidofff’s Study… [5.See enclosed]. The clock was first delivered to his house in Paris in around 1818-20, before following him to Rome, Florence and San Donato.

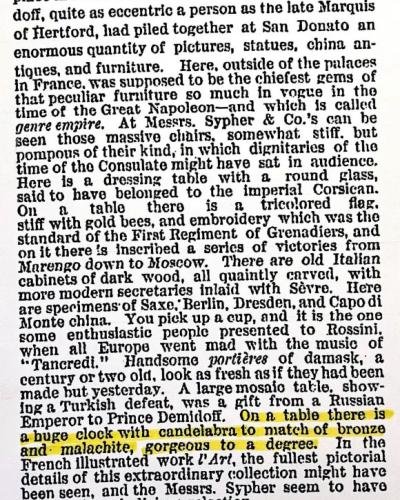

The clock was purchased by New-York based Messrs Sypher & Co from the March 15th 1880 sale of the Palace of San Donato, and exhibited in their showrooms, as the New-York Times article of October 1st 1880 reports: “A huge clock with candelabras to match, of bronze and malachite” [6.See enclosed] (The said company later became French & Co, frequented by the wealthiest American collectors of the time).

This newly discovered information concluded: the clock is in America…!

Armed with this knowledge, it was the time to approach the Hollywood movie companies…It was understood that Columbia Pictures and Warner Brothers Studio had merged their prop departments… An appointment was made to find out if their inventory included the Minin and Pozarhsky clock featured in the movies…

It was easy to find the clock in the props department of the studio. The malachite base had been stored separately… And the two were finally reunited!

With close examination, a Sypher & Co label was found attached inside the malachite base, and the bronzes were stamped with capital “D” (for Demidoff), and “THOMIRE A PARIS” !!! After all, it was Count Nicolas Demidoff’s Minin and Pozarhsky Clock… But now, also engraved with the famous Columbia Pictures inventory number: “107-6169” [7.See enclosed]

It was… one of Hollywood’s earliest art and antiques’ purchases at the time when the studios believed “the camera couldn’t lie”!

Because of low interest in historical dramas, most of Hollywood’s prop-departments of antiques were sold… The clock was purchased, and remains in a private collection.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS :

1. Still-photo from Columbia’s movie “Rusty saves A Life” 1949 – Courtesy Bison Archives

2. Ivan Martos: Sculpture of Minin & Pozarhsky on Red Square, Moscow, 1818

3. Jean-Baptiste Fortune de Fournier: Interior of the Ballroom at San Donato, 1841 – Courtesy Palazzo Pitti.

4. & 4 Bis M. Carles Pillet: Sale Catalogue “Palais de San Donato”, in: L’Objet D’Art, March 15 1880; p. 354 n°1553 – engraving of Minin & Poszarhsky’s clock.

5. V.B. Semyonov: Malachite, Sverdlovsk, 1987

6. “From the San Donato Sale”, in: The New-York Times, October 1880 – copyright The New-York Times

7. Pierre Philippe Thomire: Count Nicolas Demidoff’s Minin & Poszarhsky Clock, ca. 1818-20 – Private Collection